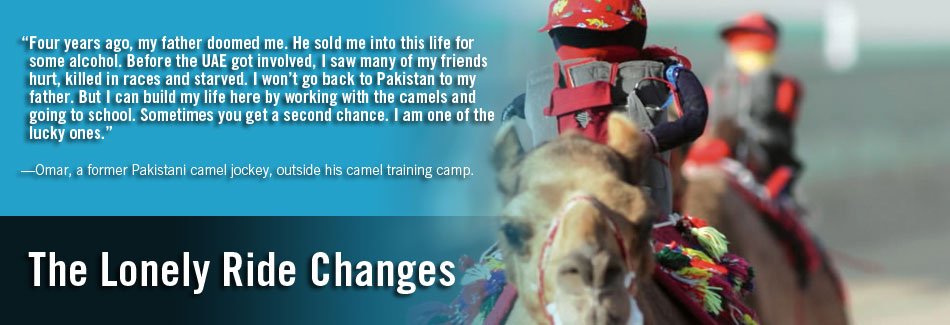

Desirable because they are light in weight, easy to feed and without a voice, the boys are destined for lives worse than the ones they left. Mental and physical brutality await when losing a race. There’s a lack of, or no, educational system for the boys, who are disposed of once they become too big to ride.

Ray of Hope

The sport, once the butt of worldwide jokes, is not to be taken lightly. Camel racing is now big business, with top producing camels worth over $1 million dollars. But with the vulnerable children being injured and killed each year and whispers of prevalent beatings and systematic food deprivation to reduce weight and growth, there has been mounting pressure from Western and Asian groups to impose reform.

In 2005, restrictions on the use of child camel jockeys in the UAE were imposed, stating that camel jockeys must not be younger than 15 years old or weigh less than 100 pounds. These restrictions looked fine on paper, but watchdogs reported that authorities banned photography at the racetracks to prevent continued abuse from being documented.

The UAE government then initiated a partnership with UNICEF to identify children who were placed into this environment without their consent and to repatriate them to their countries of origin at the government’s expense. The sum of $2.7 million was initially committed to the partnership. Further, UAE President HH Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan issued a federal law banning camel jockeys under 18 and authorizing penalties of up to three years in jail and/or a minimum fine of $13,600. Penalties are doubled for repeat offenders.

The UAE launched an anti-trafficking consciousness effort with a blanket of advertising and pamphlets distribution at airports, worksites and embassies, advising potential victims on their rights and resources and warning perpetuators on the penalties involved. Law enforcement officers and prosecutors were given anti-trafficking training, with the Dubai police taking the lead in establishing a human trafficking division to investigate crimes. A 24-hour hotline was set up for victims to lodge complaints.

Going Back Is Not So Easy

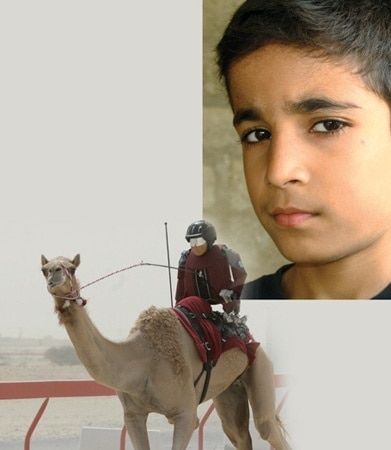

Even with all of the reforms, there is still much work to do on the psychological front. Take brothers Ahmed and Said, who immigrated to Dubai in 1999 with their father for the promise of work. Soon thereafter their father was killed in a boating accident, and the camel stable agents came calling to “suggest” that the brothers work as jockeys. With nowhere else to turn and the promise of a family lifestyle, the 10- and 6-year-old brothers took the offer.

“They promised to get in touch with our families back in Bangladesh, but they told us they couldn’t find them. They threatened to throw us in jail,” said one of the brothers. “We were scared and we followed their orders. Life was pretty miserable with only a small plate of food in the morning and at night and only water.”

With government reforms, the boys, now 18 and 14, were recently returned to their aunt and uncle, only to find that life might be just as difficult as the one they left behind. The road to re-assimilation is hard. Nearly 10 years away from their native tongue, they are finding challenges in transferring back to the Eastern Panjabi language from Arabic. They also have years of schooling to make up or face the life of a laborer. The unemployment rate is nearly 20 percent where they live.

“We want to return to Dubai and integrate into the business world there,” Said says. “We have to catch up in our education and then earn enough to travel. The only happy part is that we live with our family, and they are very supportive.”

Technology to the Rescue

The UAE is looking to eliminate all of the embarrassment of the recent developments by implementing the use of robots as jockeys for camel races. Prototypes of the mechanical lightweight jockey robots have been successfully tested, and word is that the royals, who are seeking to protect the sport and its heritage values, are pleased that the robots will eliminate the need to break the new rules.

The idea is being received positively by human rights groups, and those youngsters who cannot be re-assimilated back into their native countries can be employed as operators of the remote control jockey systems.

The UAE government then initiated a partnership with UNICEF to identify children who were placed into this environment without their consent and repatriate them to their countries of origin at the government’s expense.